Flownex Tech Tip #2

As we build more and more networks it quickly becomes tedious to enter in the same inputs many times. There are a couple methods of using global parameters to save us lots of time and clicks. In this example I am working in Flownex Version 8.12.7.4334

Refresher on Global Parameters

Global parameters are just what they sound like. Parameters defined globally for the project. These could be any type of component input; diameter, length, temp, pressure, etc.

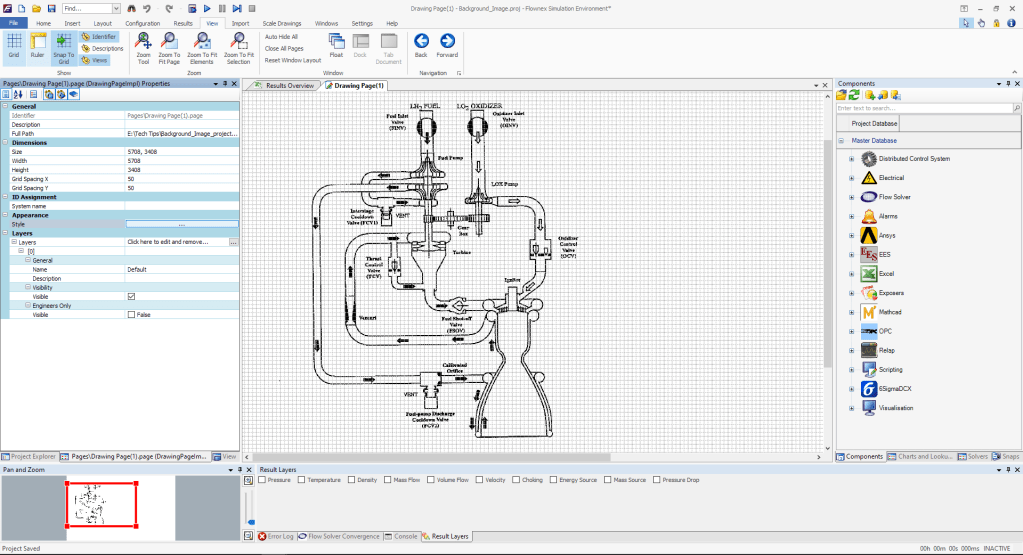

The global parameters can be found in a couple of locations. Under the configuration ribbon we can open the global parameters in a floating window which gives us a friendly interface for creating or modifying these parameters. To create a global parameter one may simply right-click in the GlobalParameters window and select Add (hint: there’s a better way!).

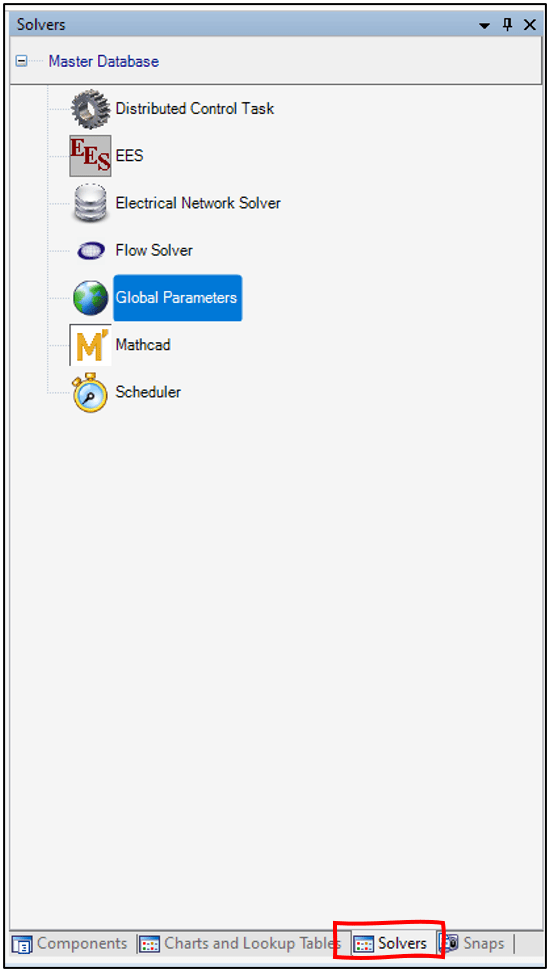

Global parameters can also be accessed in via the solver tab in a similar way to typical inputs (this is important later on).

The Quick way to add Global Parameters

We don’t really want to have to navigate to that configuration ribbon, right-click a bunch, choose names and assign units do we? Good news! There is a much faster way to add a global parameter. We can add a global parameter with minimal work by simply typing a dollar sign “$” prefacing the name of the tag in any of our component input fields! Remember to hit enter after typing the identifier.

Once a global parameter has been defined we can tie more inputs to the existing parameter by typing the dollar sign “$” and choosing the correct parameter from a drop down:

As you can see, this can be quite a time saver when building a network! The next trick utilizing global parameters will have to do with using them for actual analysis.

Using Global Parameters as Manipulatable Inputs

The default/slow way to change a global parameter would be to go to the configuration ribbon > global parameters, and manually change the value in the floating window. No thanks. This is not automated at all and requires many clicks.

The better way to utilize the global parameter as an input would be to tie the global parameter to an input sheet, parameter table (for a parametric study), or even a human machine interface component (HMI).

Global Parameters in Input Sheet

For a design variable that an analyst or engineer may change which would then remain constant (such as pipe diameter) the input sheet comes in very handy. To reference a global parameter in the input sheet recall the second method to access the global parameters and then simply drag and drop onto the input sheet:

Global Parameters in Parameter Table

If you are trying to run a parametric study where you are varying something like ambient temperature, it makes sense to use a global parameter as you may have many boundary conditions defined by a single global parameter. Similar to the input sheet this can be tied to a global parameter by a simple drag and drop operation:

Global Parameter in a Human Machine Interface

By now I expect you are catching on. The trick to defining a global parameter externally is to use the second method; solver tab > global parameters, and then drag and drop to your desired connection. In the HMI instance I’ve tied inlet mass flow to a Track Bar so that a user can dynamically change the flow rate during the solve:

Global Parameters are efficient and POWERFUL

We can use global parameters during network construction using the “$” shortcut to build our networks much more quickly and keep identical inputs the same. We can tie these global parameters to other tools to keep our user inputs all in one place, reducing clicks, and reducing the chance of forgetting to update an input.

Bonus Tips!

- Global Parameters can also be used in Designer so that you can keep your independent to dependent variable count the same (EX: Adjusting ALL pipe diameters to target a single exit flowrate)

- Global Parameters can be adjusted via transient actions (EX: Adjusting ambient temperature to model the changing temperature over the course of 24 hours).